Addressing Mental Health in Fantasy by Darrell Drake – Guest Post

Addressing Mental Health in Fantasy by Darrell Drake – Guest Post

Darrell Drake has published four books, with A Star-Reckoner’s Lot being the latest. He often finds himself inspired by his research to take on new hobbies. Birdwatching, archery, stargazing, and a heightened interest in history have all become a welcome part of his life thanks to this habit. Post contains affiliate links.

Addressing Mental Health

Preface: I am by no means offering a professional perspective on the topic at hand. However, I have done extensive research, and recommend you do your own. I’ve also drawn from personal experiences.

With the rare exception, protagonists in fantasy are often healthy individuals who are sound of mind and body. This post is concerned with the former: heroes and heroines beset by mental health issues.

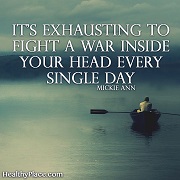

Naturally, a character struggling with mental illness may find the journey of a protagonist more of a burden than one without. By no means does that render them incapable. Too often, mental illness is polarized in its representation. More radically, the homicidal whims of a mad king; more shallowly, in a character deliberating his tankard. Fantasy needs to adopt a more realistic, researched, and most of all sympathetic portrayal. This will bring about more nuanced characters, and a better, more human representation of those souls who deal with it outside the pages.

Happy-go-lucky, sardonic, or overly brooding characters are all well and good if they suit the story—and there needn’t be a dichotomy between these dispositions and those of a mentally ill individual. However, some effort should be put forth to stay true to those suffering: out of sensitivity to their trials, and to achieve an accurate, convincing characterization.

Because they’re pertinent, and because I’m the most familiar with them, I’ll be using the heroines of A Star-Reckoner’s Lot as examples.

Let’s begin with Ashtadukht, the woman whose tale is being told. She shoulders many burdens: her body’s infirmity, the condescension of her peers, the loss of her husband and brother (consanguineous relations were not frowned upon), and the depression brought on by these burdens. As an aside, don’t mistake this description for a weak heroine; she is anything but.

As readers will come to discover, chief among Ashtadukht’s troubles is her grief. She and her husband were inseparable, and while she presses forward in some ways, her grief is the incontrovertible despot wreaking havoc on her life. It dictates her actions in ways that are both subtle and glaring; it steers her path; it transforms her. Ashtadukht was not fortunate enough to move on, and deep down, she finds herself denying it ever happened.

This reminds me of an especially poignant yet much more severe case of a daughter who simply refused to believe her mother had died. She would wait by the phone, hoping it’d ring. Eventually, this devolved into having one-sided conversations with her departed mother, vehemently denying any claims that the woman had died at all. She strode counter to reality. That is the sometimes insuperable power of grief.

The loss of a loved one affects us in ways we often cannot fathom—it scores deep, lasting blows whose scars remain for life. What follows asks a person to grow from bereavement. Perhaps to take up the pursuits of the one lost. Or to learn to cherish alone the things they had cherished together. Not everyone is capable of this; not all broken relationships allow it. But wherever a person ends up as a result of bereavement, they are undoubtedly changed. It’s important to take that into consideration when a character has lost someone close to their heart.

Moving on, Ashtadukht’s tale is rife with reasons for her depression—not the least of which being the aforementioned grief. Many will see depression as a one-dimensional emotion: something akin to but not entirely the same as sadness. Or as something, like loss, that a person can just get over with time and effort. Contrary to that misguided view, depression is multi-pronged in its assaults. Unremitting, too.

Its manifestations come and go, but they are not gone for long. Lethargy, suicidal thoughts, irritability, hopelessness, and a feeling of vacancy are but a few of the regular symptoms. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, does classify ongoing depression as both a symptom of disorders and as disorders of its own variety. Speaking in the general sense, depression can exist as a disorder or as a short term reaction to the regular nadirs of life. Regardless the reason or classification, depression smarts.

So when writing a hero or heroine suffering from something of the sort, it’s important to take the symptoms into consideration—beyond the melancholy typically assumed of the state. This doesn’t prevent a journey from being pursued. It does, however, influence the character, and in turn the pursuit. Take the time to consider whether your character’s hopelessness holds them underwater, whether they snap at others without provocation, whether suicidal thoughts make them consider wading into the oncoming horde and accepting their fate. They needn’t always give in, but readers will be grateful, the characters will be all the better for it.

Our next subject is Waray, one of Ashtadukht’s closest companions, and a perilously afflicted one at that. Mentioned earlier in passing, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders applies more actively to Waray’s disposition. While the disorders in the DSM are often defined with blurred lines (which are hotly debated and regularly changed), they do have general parameters to abide by in seeking to classify and treat disorders. Commonly, patients will exhibit co-morbidity between two or more disorders: meaning they have symptoms belonging to several.

In the case of Waray, two dominant personality disorders surface: Schizotypal and Borderline. Rather than writing strictly according to her character outline or vice versa, she was framed to some extent within in the boundaries of these disorders.

One symptom of Schizotypal Personality Disorder (SPD) is what is called an idea of reference, which involves the belief that random people or events have some importance in one’s life: that, perhaps, something is being arranged with the individual in mind. Don’t confuse it with self-importance; ideas of reference lean toward seeing evidence of one’s destiny where it clearly doesn’t belong.

Most evident in Waray are her strange idiosyncrasies, her off-kilter frame of thought, and her generally eccentric behavior. She’s endured much, been betrayed, and this only amplifies the arms-length distrust she focuses on others. Between her oftentimes turbulent relationships with her cohorts, her odd speech and thinking, and her canted interpretation of the world around her—such as the belief that she’s witnessing marital disputes between birds—Waray exhibits clear symptoms of SPD. Readers will perhaps find these symptoms most easily identified in her wayward, imaginative, and utterly absurd accounts of everyday affairs. There are, of course, more subtleties involved.

While SPD is certainly no walk in the park, Waray’s signs of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are decidedly grim, and easy to follow. She exemplifies the self-damaging, impulsive, and chaotic behavior associated with BPD. Ashtadukht considers her a dear friend, but for these reasons, she once described Waray thus: “A liability. Reckless. Eccentric. Maddening. Hoarding.” It wasn’t all bad, but you get the idea.

Dissociation plays a heavy, terrible role in Waray’s story, but that and some of her other characteristics are best left to readers to discover.

These are but two examples of how characters can suffer from mental health concerns—one more than the other–yet persist in their adventure. There may be hiatuses involved to allay the burdens of one or the other, but they both eventually press on in pursuit of their quest.

Writers dabble: that comes with the territory. We research, but we cannot possibly hold a degree in everything relevant to our stories. That considered, we owe it to our characters, our readers, and those with real mental health issues to take the time to research. And in doing so make an honest attempt at illustrating the trials involved. A sympathetic approach to mental health will invariably improve the quality of both the fantasy community and its novels.

Pages – 322

Release Date – 2nd October 2016

Format – ebook, paperback

Ashtadukht is a star-reckoner. The worst there’s ever been. Witness her treacherous journey through Iranian legends and ancient history.

Only a brave few storytellers still relate cautionary glimpses into the life of Ashtadukht, a woman who commanded the might of the constellations—if only just, and often unpredictably. They’ll stir the imagination with tales of her path to retribution. How, fraught with bereavement and a dogged illness, she criss-crossed Sassanian Iran in pursuit of creatures now believed mythical. Then, in hushed tones, what she wrought on that path.

Purchase Links