Balancing Showing and Telling by Anne Goodwin – Writing Tips

Balancing Showing and Telling by Anne Goodwin – Writing Tips

Our new segment for 2022 is for new authors/writers and written by published authors, titled – Writing Tips. These posts will be shared with you every Wednesday. Our latest post is from author Anne Goodwin on the subject ‘Balancing Showing and Telling’. This post contains affiliate links.

Balancing Showing and Telling

Show, don’t tell has become a cliché in creative writing parlance yet, when I first encountered it, it felt like discovering the earth was round. I’d been writing on and off all my life without knowing there were any rules about it, and I embraced this one with gusto. Showing – presenting the story and characters through sensory details and actions – rather than telling, helps bring the story alive for readers, but don’t just take my word for it. Chekhov has supposedly said, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining. Show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

Showing makes the experience of reading more immersive for readers, making our fiction feel real and non-fiction more vital. When we’ve practised literary art enough it can become second nature but, until we reach that stage, here are a few tips:

– Use dialogue, and make it realistic by giving different characters different speech styles.

– Avoid labelling emotions with words like sad, angry, delighted etc but show how a person feels through their behaviour and body language.

– Draw on all five senses in your descriptions: include smells, sound, textures and taste in addition to the more obvious sight.

– Bring your settings alive by showing characters in action (which can include their thoughts).

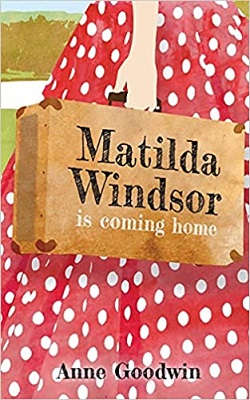

For an example of the latter, let’s consider my novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home. It’s set mostly in a long-stay psychiatric hospital, a grim Victorian edifice where Matty, the main character, has been shut away for fifty years. While readers need to be able to imagine the bricks and mortar, it seems more important that they appreciate the emotional atmosphere. I showed this primarily through the character of Janice, an idealistic young social worker who takes up post in 1989. Here she is arriving for her appointment interview:

Leaving the car park, the clock tower confirmed she’d made it with five minutes to spare. Despite being home to several hundred people, and workplace for as many staff, there wasn’t another soul in sight. An aura of subterfuge enveloped Ghyllside – of deadness – as if behind the majestic facade lurked a yawning sinkhole, as if the roses in the turning circle were made of wax. Mounting the stone steps, Janice imagined mingling with the hapless new arrivals in the hospital’s heyday a century before. The ache of rejection. The fear of never seeing a friendly face again.

A more telling version of the same event might run something like this:

Janice arrived just in time for her interview. The hospital, built in the nineteenth century, was quiet, almost dead. There was a clock tower and stone steps leading to the door.

One obvious difference between these two descriptions is that the showing version is longer. If we were to outlaw telling completely, we’d contravene another basic ‘rule’ of creative writing, which is to convey the information the reader needs to know in the most economical way.

Novice writers, having grasped the importance of showing, risk boring the reader with excessive detail. In dialogue, for example we should skip the niceties of ‘Good morning, Anne, how are you?’ and go straight to the heart of the matter. In Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, I summarised Janice’s recruitment interview in a single telly paragraph and went straight to Janice’s questions about the job, which is more relevant to the reader.

For a more detailed discussion of balancing showing and telling, including how telling is the basis of fairy tales and other oral traditions, I recommend this post by Emma Darwin.

About the Author

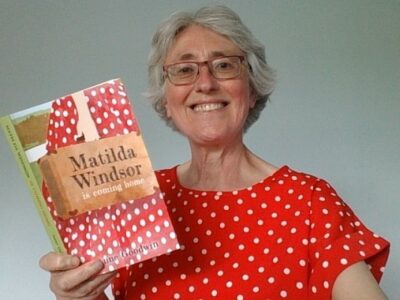

Anne Goodwin writes entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice. She is the author of three novels and a short story collection published by small independent press, Inspired Quill. Her debut novel, Sugar and Snails, about a woman who has kept her past identity a secret for thirty years, was shortlisted for the 2016 Polari First Book Prize.

Her new novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, is inspired by her previous incarnation as a clinical psychologist in a long-stay psychiatric hospital. Subscribers to her newsletter can download a free e-book of prize-winning short stories from her website below.

Author Links

TikTok

Website

Publisher – Inspired Quill

Pages – 350

Released – 29th May 2021

ISBN-13 – 978-1913117054

Format – ebook, paperback

In the dying days of the old asylums, three paths intersect.

A brother and sister separated for fifty years and the idealistic young social worker who tries to reunite them. Will truth prevail over bigotry, or will the buried secret keep family apart?

Told with compassion and humour, Anne Goodwin’s third novel is a poignant, compelling and brilliantly authentic portrayal of asylum life, with a quirky protagonist you won’t easily forget. Published by Inspired Quill.