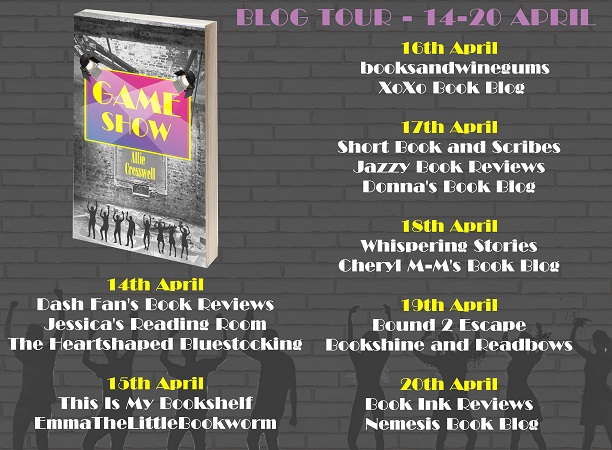

Game Show by Allie Cresswell – Extract

Game Show by Allie Cresswell – Extract

Today we welcome author Allie Cresswell on to the blog with an extract from her book, Game Show, as part of her week long blog tour. Post contains affiliate links.

Publisher – Createspace

Pages – 342

Release Date – 6th June 2013

ISBN 13 – 978-1484998229

Format – ebook, paperback

It is 1992, and in a Bosnian town a small family cowers in their basement. The Serbian militia is coming – an assorted rabble of malcontents given authority by a uniform and inflamed by the idea that they’re owed something, big-time, and the Bosnians are going to pay. When they get to the town they will ransack the houses, round up the men and rape the women. Who’s to stop them? Who’s to accuse them? Who will be left, to tell the tale?

Meanwhile, in a nondescript northern UK town a group of contestants make their way to the TV studios to take part in a radical new Game Show. There’s money to be won, and fun to be had. They’ll be able to throw off their inhibitions and do what they want because they’ll all be in disguise and no-one will ever know.

In a disturbing denouement, war and game meld into each other as action and consequence are divided, the words ‘blame’ and ‘fault’ have no meaning and impunity reigns.

Game Show asks whether the situation which fostered the Bosnian war, the genocide in Rwanda, the rise of so-called Islamic State in Syria and the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar could ever happen in the West. The answer will shock you.

Purchase Links

Amazon.co.uk – Amazon.com

Extract

The people in the besieged Bosnian towns never knew quite when the Serbian militia would come, but they knew that when they did, it would be terrifying. In this extract, ten year old Gustav has been asked to draw a picture while his mother (Majka) and grandmother (Baka) get ready for the inevitable arrival of the troops.

Gustav needed the toilet but he didn’t move. He carried on colouring as though his life depended upon it. Rasp, rasp. Baka began to sweep again, a little faster, but no less thoroughly.

‘They’re too soon. We’re not ready,’ sighed his mother, as though referring to guests who had arrived too early for dinner.

Soon. Soon.

Presently the sound of footsteps echoed outside. Heavy-booted feet. Four or five men. If Gustav had turned his head, he might have seen the boots though the high up window, standing indecently close to his house, but he kept on looking at his picture, and in fact drew the half-moon shaped window on to his house, low down near the ground. There was the sound of men talking, laughing; shockingly loud in the breath-held silence of the basement, and in the stillness Gustav could even hear the scrape of a match against a box, and the spurt of flame. Something bounced onto the windowsill, jumped through the gap and skittered onto the ground. The matchstick lay like an impostor on their floor, and the grown-ups could not have stared at it with more horror if it had been a grenade that might blow up in their faces. Then it was gone, rasp, under the bristles of Baka’s broom.

There must have been a signal; suddenly the booted feet were on the move, and Gustav could hear others walking briskly along the street. They heard a shout, and a woman’s voice protesting loudly. Gustav had finished his picture. With immense care and concentration, he laid his pencils neatly in a line on the table, in order, like a rainbow. No, not like that, rainbows don’t have black in them. Like something else; like soldiers, straight-backed and tidy. Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. Something was wrong, but Gustav couldn’t think what.

Soon, soon, they were coming soon.

He slowly rose from his chair and advanced solemnly towards Baka. Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. Nine paces. But it felt wrong, like one of the steps was a limp or a hop. Something was missing. With each step across the room he recited the colours to himself and even as he held out the picture to his grandma, they went on in his head like a mantra. Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. And suddenly the sounds of the colours were outside his head, echoing around the house as heavy footsteps overhead crossed the floor. Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. Nine paces. The same distance across the basement but travelled overhead. No hops, no limps, just firm, purposeful treads.

Soon, soon. It was going to be very soon.

Grandma, still holding the broom, took his picture in her other hand and smiled. Time had slowed down, like in a dream. Her movements had a studied deliberateness. Perhaps time would stop, perhaps soon would not come. She rested the broom handle in the crook of her arm while she folded the paper carefully and slipped it into her pocket. In this pause, the man above must have looked into the kitchen, then, quickly, time back to normal, BLACK, BROWN, GREY. BLUE, GREEN, RED. ORANGE, YELLOW, PINK. Nine footsteps down nine steps and the man was in the room. Nobody said a word.

The man himself was not extraordinary. He wore a uniform of sorts that was dirty and unkempt. The place where his regiment insignia had been was ragged, patched over with a scrap of other material, but it hung off at one side where his inexpert stitches were coming undone. A bushy, matted beard and a straggly moustache largely covered his face. His boots were filthy and clods of slush-mud fell off them as he walked, onto the clean floor. He carried a long gun slung over his shoulder by a leather strap. It looked heavy and complicated, and efficient. The man and the gun stood, like two people, in the room alongside Baka, the broom and Gustav. They looked ridiculously like a little knot of people at a cocktail party who have not been introduced and don’t know what to say.

Black, brown, grey. Blue, green, red. Orange, pink, yellow. Gustav waited in the silence that hung in the room like a smell. The man himself smelt very bad, like an animal. Now Gustav was on his feet the need to wee felt very strong, and he resisted the temptation to jiggle around on his toes. He repeated his colour mantra to keep his mind off the urge. At the man’s throat, a purple neckerchief made a bright triangle in the drab green-brown of his combat gear. The colour purple struck a chord with Gustav because it was what had been missing from his crayon collection. At that moment, Grandma lifted the broom a fraction and moved it towards the mud that had dropped from the man’s boots. As she did so, Gustav saw his purple pencil beneath the bristles, in the pile of dust and fluff. He bent to retrieve it. Before a split second had passed, the man raised one of his dirty boots and, like a penalty-taker, kicked Gustav in the stomach so he literally flew across the room and crashed into the wall. Baka raised the broom to strike the man, but too feebly, and he knocked her with his elbow so she crumpled like an empty sack behind him. He caught Majka easily as she rushed at him, holding her around her arms with his legs well apart, so her flailing feet and thrashing body were as powerless as a child’s. Adele, who had remained motionless in the corner on her crate, began to scream. Gustav, dazed and doubled up against the wall, felt the urine flood down his leg and soak his trousers.

In the commotion, more heavy boots entered the room above and began to hurry down the stairs. ‘Out!’ The first soldier pushed Majka in front of him up the steps, towards another soldier who was halfway down. Then he caught Adele by the wrist and dragged her up behind him. She stopped screaming but continued to tremble and sob as she stumbled up the steps. Baka struggled to her feet and, bent double, crossed the room to Gustav, helping him up. He was beyond tears. He tasted the iron of blood in his mouth. Gustav and Baka climbed the stairs together. Gustav tried to remember his mantra, but the colours had gone.

I have been writing stories since I could hold a pencil and by the time I was in Junior School I was writing copiously and sometimes almost legibly.

I did, however, manage a BA in English and Drama from Birmingham University and an MA in English from Queen Mary College, London. Marriage and motherhood put my writing career on hold for some years until 1992 when I began work on Game Show.

In the meantime I worked as a production manager for an educational publishing company, an educational resources copywriter, a bookkeeper for a small printing firm, and was the landlady of a country pub in Yorkshire, a small guest house in Cheshire and the proprietor of a group of boutique holiday cottages in Cumbria. Most recently I taught English Literature to Lifelong learners.

Nowadays I write as full-time as three grandchildren, a husband, two Cockapoos and a large garden will permit.

Author Links

www.allie-cresswell.com

@Alliescribbler

Facebook

Goodreads